|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The modern view of human endeavor may be summarized in many ways, as many as there are modern thinkers perhaps. Here is more of my view of what went wrong in post-modern thinking.

|

|

Thomas Kuhn explained science that way. Rather than a continuous and monotonic search for truth, he suggested that science was a sequence of paradigms, a word he later grew to detest in its popularization, each of which required revising not only the answers but the very questions being asked. (I was privileged enough to be in a college lecture hall with Thomas Kuhn.)

The post-modern view of human endeavor

seems to be the appearance of achievement,

using the language of those who achieve

without their intellectual investment.

I'm not sure they're deliberately deceitful

or themselves deceived by their own quest for membership.

Part of the post-modern "mystique" is this ambiguity

between charlatanism and hypocrisy.

The post-modern view of human endeavor

seems to be the appearance of achievement,

using the language of those who achieve

without their intellectual investment.

I'm not sure they're deliberately deceitful

or themselves deceived by their own quest for membership.

Part of the post-modern "mystique" is this ambiguity

between charlatanism and hypocrisy.

Unfortunately,

the quest for knowledge is a fragile thing.

The kinds of achievement that make it possible

for so many of us to live well

on this planet [1]

requires a social and legal infrastructure

that

takes decades, even centuries, to build.

Most of that infrastructure has eroded

in the last few decades,

at least here in the United States

where that quest has been most successful

in the past century and a half.

Unfortunately,

the quest for knowledge is a fragile thing.

The kinds of achievement that make it possible

for so many of us to live well

on this planet [1]

requires a social and legal infrastructure

that

takes decades, even centuries, to build.

Most of that infrastructure has eroded

in the last few decades,

at least here in the United States

where that quest has been most successful

in the past century and a half.

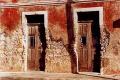

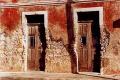

Without trying to analyze the whys and wherefores, I would like to explore my favorite doorways that seem to have slammed shut, all about the same time. Maybe it is just a coincidence that all these areas of human endeavor just happened to reach their limits around the same time. Or, maybe, something has happened to us that we have stopped looking for the next doorway.

|

|

|

|

I had passed through a doorway

from one level of hifi to the next,

from college stereo to high-end audio.

Mark Levinson's HQD (Hartley-Decca-Quad) system,

which I heard in Philadelphia,

gave the best tube systems a run for their money

and John Iverson's Electro Research electronics,

along with Andy Rappaport's line at the same time,

ended the reign of tubes.

I passed through another doorway into their world.

A couple of years later I discovered tape,

the reel-to-reel variety,

in a half-track deck (38 cm/sec, 15 inches per second)

and a pair of decent microphones.

The ability of my own recordings

to resolve the fabric of a musical event

in intonation, timbre, time, and space

was yet another doorway.

While I have heard one or two audio improvements

in the last twenty years, and

had one honest revelation in hearing the

circa-1958 Weathers turntable (mono-only, too bad),

there have been no new doorways during that time.

I believe I have reached the end of the audio journey.

Part of me wishes I could believe the delusion

and have as much fun pursuing tube-amplified digital sources

as I had when "real" audio was popular.

I suspect most of today's look-real audiophiles

are having fun at it

and have no idea there is a doorway

behind them

to the next level.

When I built my first large computer program

to simulate thousands of cellular-telephone calls

on hundreds of radio coverage areas called "cells,"

I learned to model a system by breaking it down

not only into component processes

but also into component data primitives and their attributes.

A cellular telephone system

has cells, antennas, radio channels, and calls

which became my simulation program primitives in my framework.

Each of these has descriptive features,

attributes in my framework,

such as a cell's latitude, longitude, and tower height.

Managing the dimensions of a collection of primitives

in a computer program

such as my simulation

was yet another doorway in my computing journey.

There is a community

of computer "scientists," more like religious scientologists,

in an active, energetic search for

new and different ways to program computers.

It is easy to confuse their enthusiasm

with a desire to write better programs

and to solve problems better,

but it isn't.

In fact,

when their ideas become accepted by the programming community

and lose their pioneering identity,

these academic types come up with something

even further out

as their newer and more different holy grail.

Part of me wishes I could believe the delusion

and have as much fun

instantiating objects,

developing classes,

managing program-data memory,

writing polymorphic functions,

and overloading operators

as I had when

real programmers

were solving

hard problems.

I suspect most of today's look-real programmers

are having fun at it

and have no idea there is a doorway

behind them

to the next level.

A friend exposed me

to cross country [2],

a three mile race in the woods or a park

where a bunch of guys from two high schools

would score their first five runners by place

and the team with the low score wins,

"just like golf."

(I can think of no other similarity

as

golf and cross country are about as unlike each other

as two sports can be,

but they always add "just like golf"

when describing cross country scoring

as if there were no other sport

where a low score wins.)

The marathon for me was a competitive event,

no longer against other runners

but against the clock,

a new doorway for me.

After an auspicious 3:12 initial effort

I felt a 2:50 marathon was within my grasp.

My ultimate

marathon effort is 3:03:30

and I'm pleased with that.

I'm also pleased I'm still running marathons

thirty years later [4].

There is a growing dark side of sport,

the so-called fitness movement,

that has, in my never-too-humble opinion,

missed the point.

There are two points to sport,

again in my opinion,

athletic achievement is one

and positive experience and growth are the other.

Other benefits are gravy,

nice but not the point.

I first experienced the sequence of doorways

in my pursuit of hifi.

My freshman year

I had the then-standard college stereo

of a record player, receiver, and bookshelf speakers.

The one exception is that I had a handed-down turntable

that did not have a tonearm,

so I built one out of Lego blocks (really!),

left handed to accommodate my own left handedness.

There was a clear path to better hifi in my world,

bigger speakers with more bass

and bigger receivers with more power.

There were notions of better frequency response in speakers

and lower distortion in amplifiers,

but that was it.

I first experienced the sequence of doorways

in my pursuit of hifi.

My freshman year

I had the then-standard college stereo

of a record player, receiver, and bookshelf speakers.

The one exception is that I had a handed-down turntable

that did not have a tonearm,

so I built one out of Lego blocks (really!),

left handed to accommodate my own left handedness.

There was a clear path to better hifi in my world,

bigger speakers with more bass

and bigger receivers with more power.

There were notions of better frequency response in speakers

and lower distortion in amplifiers,

but that was it.

Then I walked into my first high-end audio store,

Music and Sound Limited

when it was in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.

There was a room of pro gear,

huge multi-channel mixers and stuff like that,

and then a room of amazing consumer gear.

The Magnaplaner speakers dominated the room

along with a rack of enormous amplifiers and elegant preamplifiers

and a few turntables including the Linn Sondek LP-12.

Larry who worked there introduced himself

and played a familiar record,

Supertramp's "Crime of the Century,"

on the Linn, Audio Research, and Magnaplaner speakers.

Then I walked into my first high-end audio store,

Music and Sound Limited

when it was in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania.

There was a room of pro gear,

huge multi-channel mixers and stuff like that,

and then a room of amazing consumer gear.

The Magnaplaner speakers dominated the room

along with a rack of enormous amplifiers and elegant preamplifiers

and a few turntables including the Linn Sondek LP-12.

Larry who worked there introduced himself

and played a familiar record,

Supertramp's "Crime of the Century,"

on the Linn, Audio Research, and Magnaplaner speakers.

The sound was more:

more bass, more treble, more balance, more clarity.

The sound was also better.

But there was something qualitatively

different about it,

off the clear path of better college hifi

or anything I had heard in the suburban living rooms of my youth.

Even this multi-miked, mixed-down, processed, homogenized recording

took on life and shape when played on this wonderful machinery.

The most noticeable change for me was imaging,

that each participant in the recorded music took its place

with size and shape

in the space between the speakers.

From this and some more-natural recordings,

I learned that stereo was something beyond

left, middle, and right.

The sound was more:

more bass, more treble, more balance, more clarity.

The sound was also better.

But there was something qualitatively

different about it,

off the clear path of better college hifi

or anything I had heard in the suburban living rooms of my youth.

Even this multi-miked, mixed-down, processed, homogenized recording

took on life and shape when played on this wonderful machinery.

The most noticeable change for me was imaging,

that each participant in the recorded music took its place

with size and shape

in the space between the speakers.

From this and some more-natural recordings,

I learned that stereo was something beyond

left, middle, and right.

I learned through listening

that preamplifiers and amplifiers sounded different

and those differences were often more important

to music reproduction than speaker differences.

Even turntables make a difference,

far more than steady and accurate speed

and the absence of rumble.

At that time tubes were the king of audio electronics.

I learned through listening

that preamplifiers and amplifiers sounded different

and those differences were often more important

to music reproduction than speaker differences.

Even turntables make a difference,

far more than steady and accurate speed

and the absence of rumble.

At that time tubes were the king of audio electronics.

My Lego tonearm evolved into Erector Set (no kidding)

and eventually became the

LOCI tonearm.

Becoming a manufacturer was another doorway for me.

My Lego tonearm evolved into Erector Set (no kidding)

and eventually became the

LOCI tonearm.

Becoming a manufacturer was another doorway for me.

In doing my

own

recording

I learned to appreciate what is fundamentally wrong

with our music-production culture.

I associate it with Les Paul,

the process of recording music

geared to creating something

totally unlike what anybody would hear in live music.

The studio becomes the music venue and

big rock bands like Supertramp and Pink Floyd

give concerts where they reproduce

note-for-note and line-for-line

what they put on their records.

The music is multitrack recorded

and mixed down to stereo in "pan-pot mono"

where each track is placed along a linear path

between left and right speakers.

My recordings preserve a sense of space,

the hifi-weenie term is

image.

In doing my

own

recording

I learned to appreciate what is fundamentally wrong

with our music-production culture.

I associate it with Les Paul,

the process of recording music

geared to creating something

totally unlike what anybody would hear in live music.

The studio becomes the music venue and

big rock bands like Supertramp and Pink Floyd

give concerts where they reproduce

note-for-note and line-for-line

what they put on their records.

The music is multitrack recorded

and mixed down to stereo in "pan-pot mono"

where each track is placed along a linear path

between left and right speakers.

My recordings preserve a sense of space,

the hifi-weenie term is

image.

There is a community that has decided

through self-deception or charlatanism,

to pursue something other than musical honesty.

These are the tube weenies with the

single-ended triode crowd at the

extreme

end.

These people use the same words we used,

jargon without meaning,

form without substance,

membership in our society without investment of effort.

If they were genuinely interested in pursuing something else,

then they would have different words and different methods.

These new-age, post-modern audiophiles

want very much to be accepted into our fold and

ultimately to replace us with themselves

and to make us the outsiders.

There is a community that has decided

through self-deception or charlatanism,

to pursue something other than musical honesty.

These are the tube weenies with the

single-ended triode crowd at the

extreme

end.

These people use the same words we used,

jargon without meaning,

form without substance,

membership in our society without investment of effort.

If they were genuinely interested in pursuing something else,

then they would have different words and different methods.

These new-age, post-modern audiophiles

want very much to be accepted into our fold and

ultimately to replace us with themselves

and to make us the outsiders.

The dilution has become so ingrained

into the high-end audio community,

that I find most audio-club gatherings not much fun.

(The

Atlanta Audio Society

was a welcome exception while I lived in their territory.)

I have to wade through a crowd of look-real audiophiles

using our jargon to mean something different and less

trying to find somebody seriously interested

in what audio is really about.

In the meantime

the most fundamental core technology of audio,

reel to reel tape,

has disappeared

as the last manufacturer of analogue audio tape

has left the marketplace.

The dilution has become so ingrained

into the high-end audio community,

that I find most audio-club gatherings not much fun.

(The

Atlanta Audio Society

was a welcome exception while I lived in their territory.)

I have to wade through a crowd of look-real audiophiles

using our jargon to mean something different and less

trying to find somebody seriously interested

in what audio is really about.

In the meantime

the most fundamental core technology of audio,

reel to reel tape,

has disappeared

as the last manufacturer of analogue audio tape

has left the marketplace.

I have been singularly privileged in the realm of computers.

My high school had teletype access (110 baud telephone link)

to a mini-computer running the BASIC language,

Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instructional Code.

Our teachers were excited about the new technology

and there was a community of enthusiastic students.

Some of us were enthusiastic enough to pester

local colleges and business

to let us program their computers

that ran FORTRAN programs from punched cards.

I have been singularly privileged in the realm of computers.

My high school had teletype access (110 baud telephone link)

to a mini-computer running the BASIC language,

Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instructional Code.

Our teachers were excited about the new technology

and there was a community of enthusiastic students.

Some of us were enthusiastic enough to pester

local colleges and business

to let us program their computers

that ran FORTRAN programs from punched cards.

My two computer courses in college and graduate school

were taught by Forman Acton and Jim Wilkinson

who had been computing since the earliest days.

They were not only giants themselves

but had kept company with even-greater giants

like John von Neumann and Alan Turing.

I learned that there were fundamentals of numerical calculation

that often involved seeing the same bits and bytes of a computer

in dramatically different ways

to make the best use of them.

I went through the doorway that separated

arithmetic, vector and array solutions,

from solving equations in a numerically efficient way.

My two computer courses in college and graduate school

were taught by Forman Acton and Jim Wilkinson

who had been computing since the earliest days.

They were not only giants themselves

but had kept company with even-greater giants

like John von Neumann and Alan Turing.

I learned that there were fundamentals of numerical calculation

that often involved seeing the same bits and bytes of a computer

in dramatically different ways

to make the best use of them.

I went through the doorway that separated

arithmetic, vector and array solutions,

from solving equations in a numerically efficient way.

For two decades since then

I have applied my considerable (and immodest) skill

to computational challenges in many industries.

While I have made a lot of people a lot of money,

there have been no new doorways during that time.

I believe I have reached the end of the computing journey.

For two decades since then

I have applied my considerable (and immodest) skill

to computational challenges in many industries.

While I have made a lot of people a lot of money,

there have been no new doorways during that time.

I believe I have reached the end of the computing journey.

Gatherings of computer types fall into two classes.

The first is the Object Oriented crowd

who have Object Oriented Analysis through

Objected Oriented Zoology, A-through-Z,

in their Object Oriented studies.

The second are people who love having new and different

technologies with bigger numbers of megabytes and gigahertz

but never seem to connect any of that

with finding better answers to

the difficult and wonderful problems

computers were invented to solve.

Gatherings of computer types fall into two classes.

The first is the Object Oriented crowd

who have Object Oriented Analysis through

Objected Oriented Zoology, A-through-Z,

in their Object Oriented studies.

The second are people who love having new and different

technologies with bigger numbers of megabytes and gigahertz

but never seem to connect any of that

with finding better answers to

the difficult and wonderful problems

computers were invented to solve.

We are figuring out that

Object Oriented isn't all that

useful

and,

with a little luck and some effort,

the computing community may figure out that

Object Oriented does more harm than good.

There seem to be no new doorways

and nothing is more abhorrent to high-technology gurus

than admitting that yesterday's way of doing things

is better than what they're doing now.

I believe we have reached the end of the computing journey.

We are figuring out that

Object Oriented isn't all that

useful

and,

with a little luck and some effort,

the computing community may figure out that

Object Oriented does more harm than good.

There seem to be no new doorways

and nothing is more abhorrent to high-technology gurus

than admitting that yesterday's way of doing things

is better than what they're doing now.

I believe we have reached the end of the computing journey.

As a teenager I started running on the beach

because it seemed like something fun and challenging to do.

Soon I could run a mile, all the way

to the yellow house and back,

and even two miles.

It was a social activity if I ran with somebody

and I found I enjoyed the solitude of an ocean sunrise

as I made my way along the tide.

Once or twice my bright red hair was a target for seagulls,

a scene from Alfred Hitchcock,

but otherwise I was left alone to enjoy the mornings.

As a teenager I started running on the beach

because it seemed like something fun and challenging to do.

Soon I could run a mile, all the way

to the yellow house and back,

and even two miles.

It was a social activity if I ran with somebody

and I found I enjoyed the solitude of an ocean sunrise

as I made my way along the tide.

Once or twice my bright red hair was a target for seagulls,

a scene from Alfred Hitchcock,

but otherwise I was left alone to enjoy the mornings.

I went through two doorways that summer.

First was being part of an interscholastic athletic team

and second was training for a running race.

My view of sport was changed in many ways,

mostly in that I was now part of it.

I have been a "jock" for a third of a century.

I went through two doorways that summer.

First was being part of an interscholastic athletic team

and second was training for a running race.

My view of sport was changed in many ways,

mostly in that I was now part of it.

I have been a "jock" for a third of a century.

My freshman year in college I was left in the dust

by the cross country team

that had five runners under 25:00

for five miles [3].

A friend introduced me to the marathon

and its associated world of road racing.

I became a morning runner,

doing my thirteen miles before breakfast.

"Early to rise, early to bed,

makes a man healthy and socially dead."

Somehow I managed to keep a social life in college,

but it wasn't late at night.

My freshman year in college I was left in the dust

by the cross country team

that had five runners under 25:00

for five miles [3].

A friend introduced me to the marathon

and its associated world of road racing.

I became a morning runner,

doing my thirteen miles before breakfast.

"Early to rise, early to bed,

makes a man healthy and socially dead."

Somehow I managed to keep a social life in college,

but it wasn't late at night.

There are doorways beyond my reach,

or, perhaps, beyond where I choose to reach.

There have always been ultra-marathon races,

further than the 26.2-mile (42.2-Km) standard marathon.

Around 1978 a bunch of guys decided to come up with

a super-ultimate event called the Ironman,

2.5-mile (4 Km) swim,

112-mile (180 Km) bicycle ride, and

26.2-mile (42.2 Km) run

which evolved into an entire sport and community

of triathlon complete with Olympic representation.

These are wonderful sports

upon which I gaze with intrigue and fascination,

but of which I have no true desire to partake.

There are doorways beyond my reach,

or, perhaps, beyond where I choose to reach.

There have always been ultra-marathon races,

further than the 26.2-mile (42.2-Km) standard marathon.

Around 1978 a bunch of guys decided to come up with

a super-ultimate event called the Ironman,

2.5-mile (4 Km) swim,

112-mile (180 Km) bicycle ride, and

26.2-mile (42.2 Km) run

which evolved into an entire sport and community

of triathlon complete with Olympic representation.

These are wonderful sports

upon which I gaze with intrigue and fascination,

but of which I have no true desire to partake.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The improving health argument for sport is the easiest to dispel. The most positive assertion I can recall for physical fitness is prolongation of life roughly equal to time spent exercising. Think about this for a second: You can live sixty pleasant years or you can add ten years doing something you hate for a total of seventy years. When I first made this case, in 1977, I pointed out that the prospective exerciser would be giving up ten years of youth for ten years of old age and ten years in the twentieth century for ten years in the twenty-first, a gloomy prospect at best. (I see nothing to indicate the middle third of this century is going to reverse the steep, steady decline. The case for giving up time in the present for time in the future is indeed weak.)

Improving appearance is subjective, of course,

but there has to be a cheaper, easier way

to become attractive than hours of aerobic effort.

I suspect intelligent diet (not Atkins)

and some resistance training (lifting weights)

will get most people a healthy-looking body

without all the work.

Improving appearance is subjective, of course,

but there has to be a cheaper, easier way

to become attractive than hours of aerobic effort.

I suspect intelligent diet (not Atkins)

and some resistance training (lifting weights)

will get most people a healthy-looking body

without all the work.

The final argument for sport is feeling good. Does training feel good? Well, yes, most of the time, but there are workouts that are survived rather than savored and there are drugs that do a much better job of making people feel good than exercise can. Does racing feel good? I can remember a moment or two during a race that felt good but racing, for the most part, is a ritual of achievement, satisfaction, and soul purification through genuine challenge and discomfort, a lot of pain.

This feel-good argument touches on a hot button for me as I have heard, over and over again, how important it is do make somebody who is doing poorly not feel too bad about it. Consolation for failure may feel better than its absence, but I can assure anybody reading this that the feeling-good of doing well outshines any mitigation of feeling guilty for not doing well.

My answer to the style-fitness people buying this load of baloney

is two doorways:

The first is to compete, to race, to achieve.

Each personal record is a step up,

pride in a demonstrable achievement over previous effort.

As an aging athlete,

I have to find other measures of achievement,

but there is still the satisfaction of doing well.

There is a tremendous and wonderful transformation

that happens when fitness exercise becomes

competitive athletics at any level.

My answer to the style-fitness people buying this load of baloney

is two doorways:

The first is to compete, to race, to achieve.

Each personal record is a step up,

pride in a demonstrable achievement over previous effort.

As an aging athlete,

I have to find other measures of achievement,

but there is still the satisfaction of doing well.

There is a tremendous and wonderful transformation

that happens when fitness exercise becomes

competitive athletics at any level.

The second doorway is to broaden one's training in effort and setting. While Further isn't on the Olympic list of Swifter, Higher, and Stronger, it's still a worthy goal in training. Interval training may not be fun, but it is territory worth exploring if you want to run faster. Long runs of high intensity, called anaerobic or tempo runs, are a wonderful way to expand aerobic capacity and they can feel terrific sometimes.

Training setting is another area for exploration.

Moving to Arizona I have discovered trail running.

As an uncoordinated individual

(a "klutz" with poor footing),

I have fallen a few times

and don't really like that part of the adventure,

but trail scenery is often fantastic.

Sometimes I combine bicycling and running

or hiking and running to get to places

I would not otherwise see.

Training setting is another area for exploration.

Moving to Arizona I have discovered trail running.

As an uncoordinated individual

(a "klutz" with poor footing),

I have fallen a few times

and don't really like that part of the adventure,

but trail scenery is often fantastic.

Sometimes I combine bicycling and running

or hiking and running to get to places

I would not otherwise see.

Finally, there is the sunrise. In one form or another, my ancestral life on earth has experienced 500,000,000,000 sunrises whose beauty is imprinted on each of us through time. Each new sunrise is an uplifting and joyful experience for me, "the dawn of a new day" in cliché speak, a recognition that there are new beginnings, a chance to celebrate the coming of the sun. I don't marvel that man worshiped the sun for thousands of years, rather I wonder why we stopped.

In my world, physical achievement and experiencing the world are what sport is all about. The rest is window dressing.

On 1986 January 28

AT&T Bell Laboratories management

put a terribly incompetent director (call him James)

in charge of the cellular project.

(We were wondering what we were going to do and how

the day could get any worse

when we found out about

the Challenger space shuttle explosion the same morning.)

By the end of 1986 May only six of forty-eight people remained

in the department.

For five years

I tried other departments in AT&T Bell Laboratories

only to find the political forces that made it possible

to promote this James character

were making the rest of the labs increasingly

anti-intellectual and technophobic [6].

So my

journey

began,

more jobs,

more interesting work,

more politics,

and then

more jobs.

I opened doorways into other industries,

airlines, manufacturing,

digital radio technology, used car sales,

railroads, hotels, and retail.

I have done planes, trains, and automobiles.

I do not measure my success in controlling other people

in my workplace.

I have substantial influence over their goals

by establishing a reputation for judgment and foresight

and I exercise this influence when

there is difference of opinion.

I have met and worked with others

who measure their success by this kind of influence,

power over others,

and they not only miss the point (if there is a point)

but also erode the productivity that sustains their paycheques.

While management is a well-compensated skill

and an intriguing doorway, I remain untempted.

The daily grind of ever-increasing politics

and the frustration of being measured by how many are convinced

rather than how much is contributed

keeps me away from this dark side of career growth.

Any time I think about such a career turn,

I hear Satan's voice saying,

"Back on your heads!" [7]

Remember space travel?

Talk about doorways opening to more doorways,

what is more exciting than visiting someplace

that isn't the earth?

For those of us who fly,

there are many directions to expand ourselves.

Some achieve

instrument ratings,

commercial certification,

and air transport pilot privileges

while others long to fly more types of airplanes.

My own expansion is to fly to different airports

(up to 320 as I write this)

from big, international terminals to remote strips of dirt.

I love seeing the mountains up-close-and-personal from the air.

In 1982 I got my first job at

Bell Telephone Laboratories

in the cellular telephone systems engineering group.

Cellular was new and exciting then,

the idea of having telephones as near as our cars,

and we were expecting big things of our technological insights.

My first doorway was the usual one

of learning to work in an office setting

with similarly-smart and differently-educated people

toward a common goal.

There were many more doorways in those first four years,

all technical.

In 1982 I got my first job at

Bell Telephone Laboratories

in the cellular telephone systems engineering group.

Cellular was new and exciting then,

the idea of having telephones as near as our cars,

and we were expecting big things of our technological insights.

My first doorway was the usual one

of learning to work in an office setting

with similarly-smart and differently-educated people

toward a common goal.

There were many more doorways in those first four years,

all technical.

•

I did the math supporting a business case for technology innovation.

•

I wrote analysis software

to understand system growth [5]

•

I developed The Adam style of programming

for my first large software project.

•

I did my first large-scale combinatorial optimization.

•

I got non-technical people excited about decision support in cellular.

•

I wrote decision support software used by others that endured.

•

I even wrote interactive decision support software.

These doorways were wonderful

and each time I did a job superlatively well

I got to open the next doorway.

These doorways were wonderful

and each time I did a job superlatively well

I got to open the next doorway.

There are two professional doorways I happily leave unopened.

Power and management

are challenges of people rather than productivity.

As corporate America has emphasized those skills

over the pride of accomplishment,

we have paid the price

both materially and socially.

There are two professional doorways I happily leave unopened.

Power and management

are challenges of people rather than productivity.

As corporate America has emphasized those skills

over the pride of accomplishment,

we have paid the price

both materially and socially.

Companies today clearly value management more than

technical achievement to the point of the absurd.

I had to fight for the parking privileges associated with my rank

at one company

where I worked regularly with people in four different buildings

(other than the one where I was officially based).

It clearly bothered them that a mere technical person

could share in management privilege,

never mind that my work earned and saved a lot of money

and that I could do more of it

if I could park near the people with whom I was working.

Companies today clearly value management more than

technical achievement to the point of the absurd.

I had to fight for the parking privileges associated with my rank

at one company

where I worked regularly with people in four different buildings

(other than the one where I was officially based).

It clearly bothered them that a mere technical person

could share in management privilege,

never mind that my work earned and saved a lot of money

and that I could do more of it

if I could park near the people with whom I was working.

The old doorways are still exciting to many of us.

The Wright brothers flew on 1903 December 16

and, a century later,

half a million Americans and who-knows-how-many worldwide

still take pleasure flying airplanes.

The old doorways are still exciting to many of us.

The Wright brothers flew on 1903 December 16

and, a century later,

half a million Americans and who-knows-how-many worldwide

still take pleasure flying airplanes.

|

|

There is a sequence of doorways

humanity went through to get to the moon.

We learned to fly into space where there is no air,

we learned to orbit the earth,

we learned to get to the moon and back,

and, finally, learned to land there

so we could walk around and collect some rocks to bring home.

What a night 1969 July 20 was for all of humanity!

There is a sequence of doorways

humanity went through to get to the moon.

We learned to fly into space where there is no air,

we learned to orbit the earth,

we learned to get to the moon and back,

and, finally, learned to land there

so we could walk around and collect some rocks to bring home.

What a night 1969 July 20 was for all of humanity!

The doorway of interplanetary travel beckons, to Mars specifically and to the other planets more generally. The notion of watching a human being walking on the red planet is an exciting one to my generation.

There are two major parties in the United States today,

the Democratic-Republicans with 99% of the vote

and the Liberatarians with most of the other 1%.

Rather than use Stalin's brute-force techniques, the DRs use

a technique of pseudo-choice.

Let me explain with two examples:

After ten years marooned on a deserted island

a guy (always a "guy," never a "person" or a "man" or even a "fellow")

is rescued and they find three large huts he built.

The first, he says, is where he lived,

and the second is a temple he built for worship.

The third?

He explains,

"Oh, that's the temple where I won't go."

So what's the point?

That Americans feel comfortable when they're making a choice,

even a contrived choice.

So we create two leagues,

National and American,

Democratic and Republican,

Us and Them,

so people feel they have a choice

in whatever world series is being presented to them.

It allows them to avoid the reality

that there is one community of political force

in the United States.

("No matter how you vote, the government gets elected.")

Medical scholars seldom debate how much cancer is the right amount,

yet economist and political scientologists wax on and on

about the optimal amount of political intervention

in people's lives.

I went through a doorway when I realized

that people, even stupid people,

tend to run their own lives

better than political do-gooders.

Part of me wishes I could really get into the

two pseudo-parties in the United States,

really to care whether it's elephants or asses in power,

but the last presidential election should have

convinced anybody

that it just isn't so.

The real debate is more or less government

and not which faction gets to mess things up.

There is a common theme in all these journeys,

that whatever progress was being made

seemed to slow down and stop

around the same time,

around thirty years ago.

The term I have heard and embraced

for this revoluting new attitude is

post-modern,

a wonderfully oxymoronic term

(how can anything be newer than modern?)

for the subtle, deliberate

deceit,

of our age.

More than cheap energy disappeared in the fall

of 1973 [9].

The U.S. space program lost its vitality

and would be reborn only a shadow of its former self.

Somehow, a thriving manufacturing economy

ground to a halt.

The skies of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

once dirty-gray with soot and pollution,

are now azure blue behind a gleaming-glass skyline

as a working-class, productive economy

has been replaced with new-age business types

buying and trading companies

whose names now only allude to productivity and value.

We achieved this ecological wonder

through economic depravity,

by eliminating all those dirty-gray, sooty manufacturing industries

and their associated jobs and opportunities

for industrious Americans who are now out of work.

Whether our contemporary pundits notice it or not,

our old technologies are doing less for us and

our new technologies have become instruments

of psychological and social torture.

My first electronic-mail account was

ROSENBERG@SCORE

in 1979

before they added all the extra dots at the end.

I enjoy the universality of e-mail today,

but we are plumbing the depths of public manners

in the sheer volume of unwanted "spam" e-mail.

How many hours per day do people spend

dealing with unwanted and dishonest communications

exhorting them to buy stuff they don't want

and fishing for their credit card and bank account numbers?

The political scene has always been silly,

nothing new here,

and our American "founding fathers" figured out

that the only better government was smaller government.

They were smart enough to install limitations on government

and their successors were foolish enough to remove them.

The political scene has always been silly,

nothing new here,

and our American "founding fathers" figured out

that the only better government was smaller government.

They were smart enough to install limitations on government

and their successors were foolish enough to remove them.

I walked into a hifi store one day

and noticed they had a pair of Ohm "F" speakers.

I knew they didn't carry the Ohm line,

so I asked what the F's were doing there.

It turns out the representative from Infinity

brought them to sell their Monitor speakers against.

I walked into a hifi store one day

and noticed they had a pair of Ohm "F" speakers.

I knew they didn't carry the Ohm line,

so I asked what the F's were doing there.

It turns out the representative from Infinity

brought them to sell their Monitor speakers against.

They say a young person who is not liberal has no heart

and an old person who is not conservative has no brain.

I was the big-hearted young liberal

until my freshman year when I read

The Machinery of Freedom,

subtitled Guide to a Radical Capitalism,

by David Friedman.

It presented a series of logical and practical arguments why,

in the presence of a system of private property,

the only better government is less government.

They say a young person who is not liberal has no heart

and an old person who is not conservative has no brain.

I was the big-hearted young liberal

until my freshman year when I read

The Machinery of Freedom,

subtitled Guide to a Radical Capitalism,

by David Friedman.

It presented a series of logical and practical arguments why,

in the presence of a system of private property,

the only better government is less government.

I learned from the neural-network world [8]

that it doesn't take a very strong tendency

to point a complex system in its intended direction.

Similarly,

it doesn't take a very strong moral compass

for people to do generally the right thing,

and it's very hard for politicians to resist

temptation to do the wrong thing.

I learned from the neural-network world [8]

that it doesn't take a very strong tendency

to point a complex system in its intended direction.

Similarly,

it doesn't take a very strong moral compass

for people to do generally the right thing,

and it's very hard for politicians to resist

temptation to do the wrong thing.

I put a date on all this,

1973 October 17.

In response to United States support of Israel in the last war,

the Arab, oil-producing nations cut off their supply of oil

to the United States.

Thanks to ridiculous regulation of oil prices

and atomic power plants (now called "nuclear") from 1969,

the U.S. became and has remained dependent on foreign oil.

The future

brightly lit with atomic fission and, later, hydrogen fusion

disappeared from our planning

along with many other aspects of the American dream.

I put a date on all this,

1973 October 17.

In response to United States support of Israel in the last war,

the Arab, oil-producing nations cut off their supply of oil

to the United States.

Thanks to ridiculous regulation of oil prices

and atomic power plants (now called "nuclear") from 1969,

the U.S. became and has remained dependent on foreign oil.

The future

brightly lit with atomic fission and, later, hydrogen fusion

disappeared from our planning

along with many other aspects of the American dream.

It has taken a generation for the reality of these changes to sink in.

Ayn Rand waxed lyrical about ideas and their impact,

in her book Atlas Shrugged

smart engineers vanish and nobody notices,

an important philosopher vanishes and nobody notices,

but folks notice things don't work anymore.

What's funny about post-modern times

is that we didn't have to quit.

The powers that run our society

got rid of

the smart engineers and important philosophers

and don't even notice that things aren't working.

Ask yourself how much you could trust a company

that pays more for an MBA than a Ph.D.

It has taken a generation for the reality of these changes to sink in.

Ayn Rand waxed lyrical about ideas and their impact,

in her book Atlas Shrugged

smart engineers vanish and nobody notices,

an important philosopher vanishes and nobody notices,

but folks notice things don't work anymore.

What's funny about post-modern times

is that we didn't have to quit.

The powers that run our society

got rid of

the smart engineers and important philosophers

and don't even notice that things aren't working.

Ask yourself how much you could trust a company

that pays more for an MBA than a Ph.D.

I worked on cellular telephone technology

1982-1986 when it was brand new

and 1996-1997 when it was more mature.

None of us envisioned what an instrument of rudeness it would become.

During my last Philadelphia Orchestra concert

in the Academy of Music

(before they moved to the not-as-good-sounding new hall),

the piano soloist had to wait during his cadenza

for somebody's cell phone to stop ringing.

Kieth Jarrett was similarly patient

when I heard him in Atlanta.

Ask any random person what he thinks of cell phones

and the diatribe usually starts with

"Don't get me started ..."

and ends with

"I can't believe they're so rude."

I worked on cellular telephone technology

1982-1986 when it was brand new

and 1996-1997 when it was more mature.

None of us envisioned what an instrument of rudeness it would become.

During my last Philadelphia Orchestra concert

in the Academy of Music

(before they moved to the not-as-good-sounding new hall),

the piano soloist had to wait during his cadenza

for somebody's cell phone to stop ringing.

Kieth Jarrett was similarly patient

when I heard him in Atlanta.

Ask any random person what he thinks of cell phones

and the diatribe usually starts with

"Don't get me started ..."

and ends with

"I can't believe they're so rude."

|

|

A friend recommends Alan Cooper's

The Inmates are Running the Asylum

to point out that what's wrong with most of our technology

is that it was designed to satisfy engineers

rather than to work well for the rest of us.

I believe there is a deeper problem

with most of our technology, that it wasn't designed at all.

The next time you drive a General Motors

car [10],

ask yourself not who designed it for what purpose

but whether it was designed at all.

I wish I had a pat answer.

It seems like everything went

wrong

at the same time,

suggesting a rash of symptoms from a single ailment,

but I have no specific diagnosis to offer.

Let me suggest we can look behind us for the next doorway.

The next doorway comes from where we were

rather than where we are.

This is a vital revelation in making our world better again.

We can get there by admitting we made mistakes

(the approach I prefer)

or by finding ways to dress the old ways up

so they look New and Improved.

(There's an expression for you: "new and improved."

If it's new,

then how can it be improved ?)

The road to happiness (either material or spiritual)

is not found in megapixels, gigahertz, or terabytes,

faster downloads of better images of the same sludge we get now.

I don't know what's really better,

but I do know where we're going isn't where it's at.

It isn't in audio (tubes),

computers (objected orientated stuff), or

athletics (the fitness movement).

The joy is gone.

Let me suggest some tweaks

that will make right much of what is wrong.

Let us keep a gentle bias toward

While this may sound self-serving

(after all, I'm conservative enough (A)

and I have survived long enough (B)

to be firmly in the "old" category on the first two),

my entire career has been based

on proposing new ways of doing things (C)

and telling people (D) how to do their jobs better.

I expect and encourage resistance

as it is discussions between

the proposers of new ideas and people doing it the old way

that turns wise guys into a smart guys.

The list of four so far (A-D) gives enough of a compass

to turn our chaotic world into something useful

over the long haul,

but I would add

more

biases to get there faster.

I would add

"So, Adam, you're so smart,

things were so good,

our society went to pot,

tell us how to get back to the garden."

"So, Adam, you're so smart,

things were so good,

our society went to pot,

tell us how to get back to the garden."

(A) old over new,

(B) old over young,

(C) working over proposed,

and

(D) doing over talking.

Most of what we did wrong in the last three decades

is blind acceptance of new ideas

that never met the burden of proof that they were better

and paying attention to people

who don't know what they're talking about.

Most of the new ideas don't work as well as the old ideas

and many of them don't work at all.

Most of what we did wrong in the last three decades

is blind acceptance of new ideas

that never met the burden of proof that they were better

and paying attention to people

who don't know what they're talking about.

Most of the new ideas don't work as well as the old ideas

and many of them don't work at all.

(E) interaction over isolation,

(N) intuitive thinking over sensory facts,

(T) logic over emotion in making decisions,

and

(J) achievement over process.

These trends [11]

direct a community's energy toward productivity.

Finally, in case it needs saying and repeating,

Maintaining these attitudes, biases, prejudices, or whatever we want to call them, will not only restore the strength of character we had but allow us to open yet more doorways.

What is on the other side of the door? I don't know, I'll let you know when I get there, and I believe it's something wonderful. After all, the doorways have been wonderful in the past.

|

|

|

|

|

18:47:26 Mountain Standard Time (MST). 693 visits to this web page. |

1.

That so many of us don't live so well

is more a product of politics

than any shortcoming of engineering and technology.

We technologists have built a world

that can sustain in comfort

our current population and quite a few more.

2.

Like many good things in life,

I started running with a challenge.

I was on the who-needs-sports side of the lunch table

and a Junior-Varsity-runner friend leaned over and said,

"Well, at least I'm in shape.

I'll bet you a quarter you can't run an eight minute mile."

I ended up winning the bet,

running through the spring,

recruited by a desperate coach (still a good friend today),

surviving as a JV member of a winless team,

and being a Varsity member of a respectable team my senior year.

3.

When the regular cross country guys at college

left me in their wake,

one fellow said,

"Why don't you run with the slow half milers?"

They may have been on the slower end of the cross country squad,

but I didn't think they were that slow.

Jeff was 1:53, Charlie was 1:51,

and Craig Masback was 1:49,

not too slow in my book.

4.

I would regard my 3:03:30 marathon

(6:59.9 per mile and I don't round it off

to seven minutes)

as ultimate as I am seriously unlikely to run that well again.

My most recent marathon was in 2001,

a few years ago I admit.

I'm still running cross country races and

I'm pretty sure my last marathon is still ahead of me.

5.

My first business case in 1983 became an analysis

of cellular telephone technology alternatives

with a program that figured out how to add cells

to satisfy subscriber demand growth.

The program was called AUTOGROW

(for Autoplex Growth) and it was used for various purposes

from 1983 through 1998, a fifteen year life.

It answered several fundamental questions about

design and technology choices

and demonstrated with actual radio channel counts and coverage

the efficacy of some of our more exotic frequency reuse schemes.

6.

Anti-intellectual and technophobic,

maybe not by the standards of the local pub,

but certainly by the standards

of Bell Telephone Laboratories.

7.

A rather bad man dies and meets Satan in a room with three doors.

Satan explains, "I have good news and bad news. The bad news

is that you have to spend eternity behind one of these doors. But,

the good news is that you can take a peek behind each and take your

choice."

8.

It's an ill wind that blows no good.

Even the sixty years of fluff that neural networks

have bestowed upon us,

diverting effort from more useful work

in my well-educated and well-experienced opinion,

dropped this pearl in my lap.

It was a demonstration a friend showed me

that a feeble random-feedback system

toward getting the indicated "right" answer

was enough for the system to find it.

9.

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)

has the slogan that electricity would be

"to cheap to meter."

10.

GM has most of the rental-car market.

That means that most of us regularly sample their product

whether we want to or not.

What a wonderful market-exposure opportunity for General Motors.

It's too bad the cars aren't fun to drive.

Maybe they should require every GM employee

to drive a Toyota Camry for two weeks.

11.

Readers may notice the pattern of these suggests

the personality type classifications of

Isabel Myers and Katherine Briggs

and should not be surprised that I fall into

their ENTJ personality-type classification.

So, the man opened the first door and saw a room full of people,

standing on their heads on a concrete floor. Not very nice, he

thought.

Opening the second door, he saw a room full of people standing on

their heads on a wooden floor. Better, he thought, but best to check

the last door.

Upon opening the last door, he saw a room full of people, standing

waist-deep in excrement and sipping coffee.

"Of the three, this one looks best," he said and waded in to get

something to drink while Satan closed the door.

A few minutes later the door opened, Satan stuck his head in and

said, "Ok, coffee break's over, back on your heads!"